Introduction

Because English is taught as a Foreign Language (EFL) in Mexico, many language professionals and practitioners face the dilemma of whether to implement the English-only policy known as a monolingual approach or a bilingual approach in which the students’ mother tongue (L1) is employed as a learning aid. Although this issue has been debated since the late 1900s, an agreement has not been reached even with Communicative Approaches (Nation, 2003). For instance, there are still many arguments alleging, on one hand, that EFL classes should be delivered only in the second language (L2) to help emulate the natural way in which the first language is acquired. Then, the learning of L2 will be developed in a positive way by increasing students’ access to positive input and exposure to the target language as much as possible (Ellis, 2005). However, strong psycholinguistic arguments support the notion that both L1 and L2 cannot be separated from learners’ internal language system or interlanguage. Thus, students’ mother tongue can be employed to enhance language development since it will provide students with a source of embodied and scaffolded input (Cook, 2001; Crawford, 2004). Along the same line, Atkinson (1983), and Copland & Neokleous (2011) suggest that the role of the mother tongue should be considered in the classroom since their research showed that it might have a vital impact on students’ learning outcome.

Under these opposing views, this research article reports the results of a study aimed to explore students’ preferences and perspectives towards the use of English as the only means of instruction and the use of their native language as a teaching tool or aid. In order to provide further insights on both the monolingual and bilingual approaches, a theoretical background is presented to offer a brief description of how some current teaching practices have either favored or disfavored bilingual or monolingual policies for language learning. Additionally, results obtained from research studies on this matter will be provided to describe some salient arguments to support and reflect upon each approach under debate.

Theoretical background

Based on comments made by students and professors from our current teaching context at the Center of Social Sciences and Humanities at the University of Guadalajara, it is possible to identify two main EFL teaching practices: bilingual and monolingual language instruction. In other words, teachers either include or ban the use of the mother tongue in their classroom. For instance, some English practitioners favor the idea of translating language samples from L2 to L1, or simply relying on the mother tongue to explain grammar, vocabulary, or giving task instructions. On the other hand, other English language professors support the premise of “total immersion” into the target language with the idea that students will learn the target language as if it were their first language. Hence, under this premise, little or no L1 is used in class.

The idea behind implementing a monolingual approach is to promote extensive L2 input and interaction among learners to maximize the quantity and quality of the target language during class instruction. Thus, the use of students’ mother tongue is not allowed. The key argument that excludes the use of L1 in class is helping students to develop and build their own language system (Ellis, 2005). In fact, this claim is supported under the assumption that learning is less valuable than acquisition and that the latter only occurs by emulating the way children acquire their native language in a natural and unconscious way, with no analysis or translation (Krashen, 1982). Therefore, a student’s mother tongue has no role in learning English in an EFL context since it reduces opportunities to expose students to valuable input in the L2. Similarly, other supporters of the monolingual approach strongly believe that the use of students’ mother tongue in the classroom will make them more dependent on it, and they will not make an effort to understand meaning through contextual cues (Ellis, 2005). In Celce-Murcia’s (2001) terms, with a teaching approach in which the use of translation is promoted, the ability to use the target language in communication will decrease and the opportunities of interaction with members of the target language will be reduced. Hence, it can be added that the followers of the monolingual approach claim that the best way to learn a language is only through speaking it and that learners do not need to know the exact meaning of each utterance they encounter (Littlewood, 1981; Turnbull, 2011).

On the other hand, advocates of the bilingual approach such as Cook (2001), Macaro (2005), Nation (2003), and Widdowson (2003), acknowledge the positive role of students’ mother tongue as a cognitive support element in the process of language development. They assume that the use of L1 is an unconscious and natural feature of students’ interlanguage systems (Selinker, 1972) in which the L1 and L2 systems interact in a bidirectional way during the process of language learning. That is, when students are learning a second language, there is a psychological process in the human brain that unconsciously makes learners access and employ all linguistic knowledge in L1 in the attempt to understand and learn the target language (Selinker, 1972). In fact, the main positive benefit of using the L1 in the classroom is the possibility to give students the chance to express themselves clearly in a relaxed environment since it helps them to express solidarity and empathy and reduce the affective filter (Levine, 2003). Besides, as mentioned in input and output processing models for language learning, L1 assists students in the process of negotiation of meaning with speakers who share knowledge of the native language (Gass & Selinker, 2001). Also, by using students’ L1 in class, instructors may benefit from the time saved in trying to convey meaning, giving instructions, or implementing class management policies aimed to maintain discipline and positive rapport in class (Richards & Rogers, 2001).

Having discussed pros and cons of L1 use in the EFL classroom, it is also necessary to discuss the middle ground as well. Authors such as Nation (2003) propose a balanced approach in which the use of L2 is encouraged along with the L1 but only in a limited way; otherwise, the learning of L2 will mainly rely on translations and in some cases will undermine the importance of using L2 in the class. In addition, if L2 is limited, students’ will not have opportunities to identify levels of socio-pragmatic knowledge of the target language. Nation also claims that if the classroom is the only place for students to practice, it is better to increase the opportunities for L2 practice and reduce the use of L1 only as a teaching aid to help students convey meaning.

As follows, a series of studies either favoring or disfavoring the use of students’ mother tongue are presented to provide some useful visions and examples on this study matter. To start with some examples, a study conducted by Schweers (1999) at a Puerto Rican university found that students and professors using Spanish as L1 in an English course reported a high preference for using their mother tongue as part of the means of instruction. In addition, in a qualitative study, Levine (2003) described the attitudes of university professors and students using English as their native language as learning tool to teach and learn French, German, and Spanish as a foreign language. The results showed that teachers and students used their first language to discuss class assignments, course policies, clarify task instructions, and explain grammar or vocabulary during class. These findings demonstrate that L1 is used to aid the process of language learning. In a study conducted in an English language course with students with different multicultural backgrounds, Krieger (2005) observed that by giving students the option of using their L1 with peers who shared same mother tongue, students gained confidence in their language practice and also increased their test scores on achievement tests. This suggests that students’ first language could be used as a tool that can enhance their language learning process. In Seedhouse’s (2004) study about interactional architecture in class, he found that the use of L1 had a positive impact on the learning process by helping students accomplish cross-cultural discussions and language analysis of error correction in clarification of meaning during interactions. In a study oriented to learn about teachers’ beliefs and factors associated with the use of the native and target language regarding language teaching, Bateman (2008) found that some teachers used the native language to avoid the use of the target language, while others used their L1 intentionally due to fatigue, lack of time, linguistic limitations, and learners’ level among other reasons. Similarly, Thompson and Harrison (2014) video-recorded and analyzed ESL classes at university levels to identify the main motivations that Spanish-speaking teachers had for switching to their native language during class instructions. The main reasons identified for L1 language shifting were to explain vocabulary meaning and grammar rules, class management, establish rapport, check comprehension, and maintain class motivation.

On the contrary, other authors claim that the use of the native language as a means of instruction can be detrimental in the process of language learning since they believe that the opportunities that students have for oral and written production in L2 are limited to class practice and for that reason the use of L1 should be banned. For instance, Koucká (2007) analyzed the frequency and the reasons for which English instructors used instances of L1 during class. In this study, results indicated that teachers overused students’ mother tongue in the English class, revealing that students were not given opportunities for meaningful input, output, and error correction. Moreover, it has been found that due to the structural divergences between English and the students’ native language, the idea of using L1 may lead to incorrect translation of some lexical items that may result in language errors and misconceptions (Sharma, 2010). Similarly, in a study conducted by Dam (2010) he observed that in his English as Foreign Language (EFL) speaking classes, the use of Spanish led students to make grammar errors with patterns borrowed from their mother tongue and used in their EFL speaking practice activities. The position of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) in 2010 is that language educators should use the target language as exclusively as possible at all levels of instruction due to the fact that consistent and comprehensible input during time class is fundamental for the language development process.

The study

An exploratory study was carried out to obtain data from students who have previously received English instruction in prior course levels with language educators who followed either a monolingual or a bilingual balanced language teaching policy at the Campus of Social Sciences and Humanities (CUCSH) at the University of Guadalajara in Mexico.

Participants

A total of 34 students, 23 females and 11 males were invited to participate voluntarily in this study. Participants’ age ranged from 18 to 24 years old, with a mean age of 21 years old. However, data were only analyzed from 27 students who reported that they had previously received class instruction with professors who followed a monolingual or bilingual balanced approach for class instruction. More specifically, in previous levels only 27 students had received class instruction with no employment or some encouragement of their mother tongue during class instruction. The other seven remaining students reported that they had only experienced class instructions under the bilingual balanced approach. These undergraduate students were enrolled in two intermediate level English courses at CUCSH Campus of Social Sciences and Humanities. These English courses are delivered as mandatory school subjects and are part of the school curriculum for some degrees such as Law, Social Work, Sociology, Geography, and History, among others.

Data collection

In order to obtain data, a questionnaire with four questions was administered in the students’ mother tongue. The questionnaire contained polar and multiple-choice questions that allowed us to learn about students’ perspectives and preferences for the monolingual or bilingual balanced language policies in English language classrooms. More specifically, in question number one, students were invited to select between an English-only language policy or a balanced approach for language instruction. If answers supported the monolingual perspective, students were asked to answer question number two, or answer question number three if the answer favored the use of a little bit of Spanish as means of instruction. These two questions included six multiple choice statements in which students only had to select three main reasons that might support their answers in question number one. As for question number four, all participants in the study were told to select three main situations in which they considered the use of their mother tongue as a necessary condition in their English course. This questionnaire was anonymously delivered at the beginning of the semester during class time upon consent of the students (see Appendix, 1).

Results

The information collected from the questionnaires with the participation of 27 respondents is described and expressed in the subsequent graphs.

As mentioned, the first question addressed students’ preference for selecting the two options which were: a) receiving class instruction only in English or b) receiving class instruction in English with a little bit of Spanish.

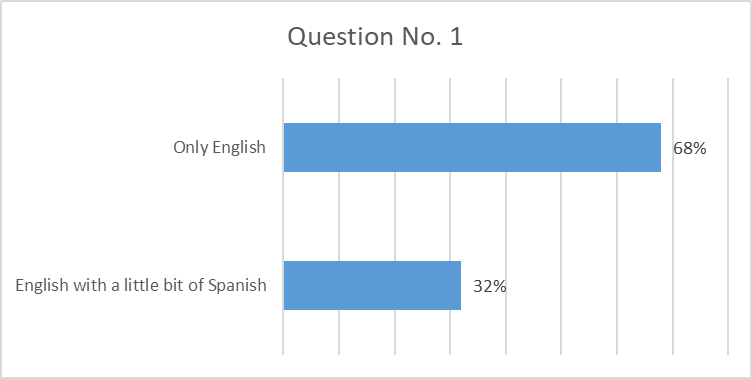

Graph 1. Do you think classes should be taught ONLY in English? Or in English with a little bit of Spanish?

Data displayed in Graph 1 above show that 68% of the students expressed a higher preference towards an English-only language policy for class instructions. As for the remaining 32%, participants reported interest in receiving class instruction in English with perhaps a little bit of Spanish. These results suggest that students who participated in the study favored the monolingual approach over the bilingual approach but exhibited slight interest in relying on their mother tongue as the means of instruction. This tendency may call for the need to mainly support the use of English at least in these two courses and perhaps leave some room for L1 when students request it. Nevertheless, because the sample of the study is not representative of the student population at the university, generalizations about the whole teaching context cannot be made.

Respondents for question two were only those students who selected the option a), favoring the English-only language policy as a means of instruction. In this question, students selected only three from the six options provided to indicate the main reasons to learn under the monolingual approach.

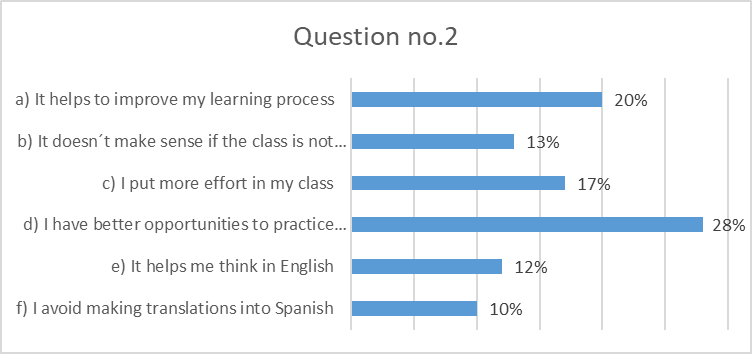

Graph 2. Main reasons to learn under a monolingual approach

Results in Graph 2 provide information about the percentage (68%) of students who reported preference for receiving class instruction under a monolingual model indicating that all the six reasons provided were chosen and proven to be important. Nonetheless, the most popular option was letter d) with a 28%, indicating that the idea of having classes only in English gives students’ better opportunities to practice the language. The second most frequent option was letter a) with a 20%, considering the use of the target language as a useful element in their learning process. The third most prevalent answer with a 17% was option c) as an opportunity to put more effort in class. The least favorite option was letter f) for avoiding making translations into Spanish. All these results agreed with the salient aspects of the monolingual approach described by advocates of the monolingual approach such as Ellis (2005), Krashen (1982), Littlewood (1981), and Turnbull (2011) presented in the theoretical background section.

On the other hand, respondents for question three were students who had selected the option b), supporting the use of a little bit of Spanish in the English course. For this question, students had to select three main reasons from a list of six options favoring the bilingual balanced approach.

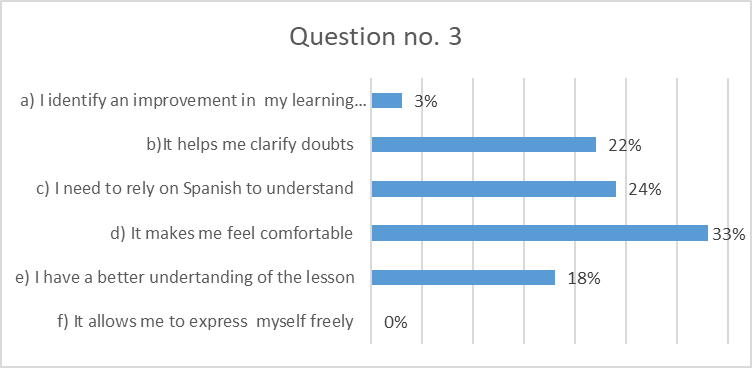

Graph 3. Main reasons to learn under a balanced approach

Graph 3 depicts the results of students’ perspectives in regards to the smaller percentage (37%) of students who voiced preference for the use of a little bit of Spanish as reported in question number one. Based on the six options provided, students selected only three options which they considered important for learning under the bilingual balanced approach. The most popular reason identified for using Spanish was option d) with a 33% indicating that Spanish makes students feel comfortable in class. The second most frequent answer selected with a 24% was the need to rely on Spanish to understand. The answer that was not chosen was option f) indicating that the use of Spanish allows students to express themselves freely. These results, along with the ones presented in Graph 4 below, support the notions provided by the followers of the monolingual approach such as Cook (2001), Macaro (2005), Nation (2003), and Widdowson (2003) presented in the theoretical background section.

As for question number four, data were obtained from the 27 participants in this study who were asked to select from a list of eight situations, three main situations in which they consider the use of Spanish as a necessary teaching tool in their English courses.

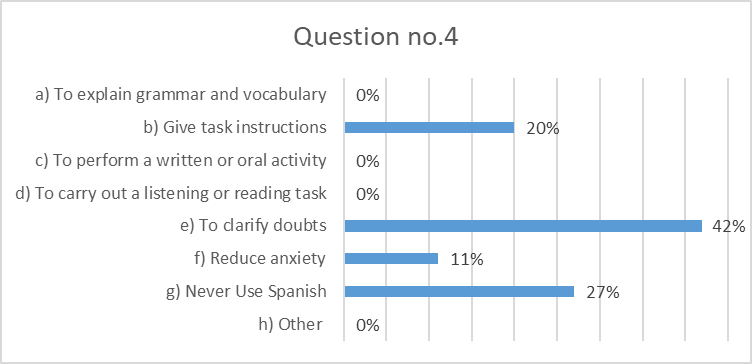

Graph 4. Situations in which some Spanish should be used as means of instruction

Similarly, to Graph 3, percentages displayed in Graph 4 show that the most desired situation selected by students for the use of Spanish in class is to clarify doubts and give task instructions as indicated with a 42% in option e) and 20% in option b). In the middle point, students indicated that classes should not be delivered in Spanish (27%). This third result correlates with the ones reported in questions one and two described above. Options provided in letters a), c), d), and h) were not selected or considered by students as activities to be delivered in mother tongue.

Conclusions

This study inquired about students’ preference of either a monolingual or bilingual balanced approach as the means of class instruction. The results revealed that students expressed a higher preference for the use of English as the only language to be used as the means of instruction. As for the use of Spanish, there was slight preference towards it and those few who expressed interest only reported the need and usefulness of it only under restricted situations. These findings support Celce-Murcia’s (2001) claims that the use L1 should be used for comprehension and clarification of meaning. Also, it was found that students’ native language should not be overused because, as Nation (2003) suggests it reduces learners’ opportunities to have enriching meaningful input and output in their learning process. Also, supporting a balanced approach as language policy will increase students’ opportunities to develop strategies for negotiation of meaning with speakers who share the same native language. On the other hand, the overuse of L1 as means of instruction limits the development of social and pragmatic levels of knowledge in the target language. However, before making any final generalized claims about the usage of the target language as the only instructional language, additional studies need to be carried out to include other factors that may have influenced students’ attitudes such as teaching method employed by teachers, students’ prior experience or exposure to the language, or students’ proficiency level of English.

Nonetheless, a salient aspect to consider in this study is the fact that students’ perceptions were taken into account, whereas in most of the cases, language policies are mainly implemented relying only on data available in the literature and based on teachers’ beliefs about what they consider is best for students. Thus, the results obtained in this study may provide additional experiences to orient school policy makers or program planners in the decision to support a language policy oriented to favor a monolingual or a bilingual approach as the main means of instruction.

References

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Language (2010, May 22). Use of the target language in the classroom. https://www.actfl.org/news/position-statements/use-the-target-language-the-classroom

Atkinson, D. (1987). The mother tongue in the classroom: A neglected resource? ELT Journal, 41(4), 241-247. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/41.4.241

Bateman, B. E. (2008). Student teacher’s attitudes and beliefs about using the target language in the classroom. Foreign Language Annals, 41(1), 11-28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2008.tb03277.x

Celce-Murcia, M. (2001). Language teaching approaches: An overview. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed.), pp. 3-10.

Cook, V. (2001). Using the first language in the classroom. Canadian Modern Languages Review. 57(3), 402-423. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.57.3.402

Copland, F., & Neokleous, G. (2011). L1 to teach L2: complexities and contradictions. ELT Journal, 65(3), 270-280. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccq047

Crawford, J. (2004). Language choices in the foreign language classroom: Target language or the learners’ first language? RELC Journal, 35(1), 5-20. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F003368820403500103

Dam, P. (2010, February 17). Mother-tongue interference in Spanish-speaking English language learners’ interlanguage. Viện Việt-Học. http://www.viethoc.com/Ti-Liu/bien-khao/khao-luan/mother-tongueinterferenceinspanishspeakingenglishlanguagelearners%E2%80%99interlanguage

Ellis, R. (2005). Principles of instructed language learning. System, 33(2), 209-224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2004.12.006

Gass, S. M., & Selinker, L. (2001). Second language acquisition. An introductory course. Mahwah.

Koucká, A. (2007). The role of the mother tongue in English language teaching [Unpublished Master’s thesis]. University of Pardubice. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e828/cfd8ee02d9c8588e773a7d5fffd6554fcd20.pdf

Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and practices in second language acquisition. Pergamon.

Krieger, D. (2005). Teaching ESL versus EFL: Principles and practices. English Teaching Forum, 43(2), pp. 8-16. https://americanenglish.state.gov/files/ae/resource_files/05-43-2-d.pdf

Levine, G. S. (2003). Student and instructor beliefs and attitudes about target language use, first language use, anxiety: Report of a questionnaire study. Modern Language Journal. 87(3), 343-364. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4781.00194

Littlewood, W. (1981). Communicative language teaching: An introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Macaro, E. (2005). Code-switching in the L2 classroom: A communication or learning strategy. In E. Llurda (Ed.), Non-native language teachers (pp.63-84). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-24565-0_5

Nation, P. (2003). The role of the first language in foreign language learning. Asian EFL Journal, 5(2), pp.1-8. https://www.asian-efl-journal.com/main-editions-new/the-role-of-the-first-language-in-foreign-language-learning

Richards, J. C., & Rogers, T. S. (2001). Approaches and methods in language teaching (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Seedhouse. P. (2004). The interactional architecture of the language classroom. A conversation analysis perspective. Blackwell.

Selinker, L. (1972). Interlanguage. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 10(1-4). https://doi.org/10.1515/iral.1972.10.1-4.209

Schweers, C.W. (1999). The use of the mother tongue. The English Teaching Forum, 37(2). 6-9.

Sharma, B. (2010). Mother tongue use in the EFL classroom. Journal of NELTA, 11(1). 80-87.

Thompson, G.L., & Harrison, K. (2014). Language use in the foreign language classroom. Foreign Language Annals. 47(2). 321-337. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12079

Turnbull, M. (2001). There is a role for the L1 in second and foreign language teaching, but…. Canadian Modern Language Review, 57(4), 531-540.

Widdowson, H. G. (2003). Defining issues in English language teaching. Oxford University Press.